Guests: Pivot’s Kevin Tisue & Bernard Kerr

After months of speculation, Pivot’s prototype downhill bike broke cover in Lenzerheide last week. Bernard Kerr has been testing several versions of this bike through the off season—due in part to the aluminum-lugged carbon construction methods that Pivot says reduces the time required to make a rideable prototype. It also makes it easier to adjust the frame design, or as was the case here, evaluate two different suspension systems over 100+ of laps of testing.

Henry Quinney and I sat down with Pivot’s Head of Engineering and Design Kevin Tisue, and Pivot Factory Racing’s Bernard Kerr to talk about the new bike, DH racing, and more.

If you’d rather read than listen, we’ve cut down an edited version of the transcript for some of the key moments below.

Contents

• Origins of prototyping carbon bikes

• Testing and suspension

• Why two chains?

• High pivot envy?

• The evolving geometry

• Why no lugs for production?

• Testing with Bernard

• Retiring on a win?

• From prototype to production

Henry Quinney:

So let’s get into this bike itself. It is a particularly good looking bike, to be fair. It feels like 10 years ago there was maybe a lot of talk about rapid development of prototyping in carbon. And here we are with the lugged bike back once more. Was it only a matter of time before we did just settle for, not settle, but go back to road bikes 20 years ago and they were lugged carbon, right? Do you think it was only a matter of time before we came back to lugged bikes or do you think carbon didn’t come on in the ways that people had hoped potentially?

Kevin Tisue:

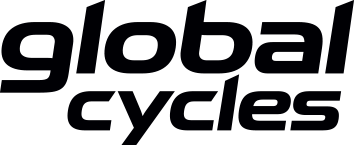

Yeah, even in a Titus cycles, Chris Cocalis, his old company, where I worked with him as well. We, we did some carbon lugged, even mountain bikes back then as well. Uh, so I don’t know in this particular case, we went with this process because we know we can develop stuff faster. And really that was the key to this was to be able to prototype things quicker so that we can actually reduce everything. Wait times going to production will get shorter and everything.

Bernard Kerr:

Titus was rad. When I was younger and I worked in a warehouse, picking and packing some things, the guy that owned that lent me a Titus road bike, which was a carbon lugged road bike. For years I would borrow this Titus and it had the same kind of [carbon] tubes with [aluminum] lugs on it years and years ago, which is quite funny.

Henry Quinney:

And so let’s actually talk about this bike in particular. First of all, Kevin, talk to me like I’m a complete idiot, all right? Don’t hold back, follow your heart. What is it? Is it a four bar DW link? Six bar? Can you just explain what this design is referred to in terms of suspension design and what the characteristics are that make it that?

Kevin Tisue:

It’s a five bar bike. No, I’m just kidding. (Laughs)

Henry Quinney:

We’re going to get into decimal places soon.

Kevin Tisue:

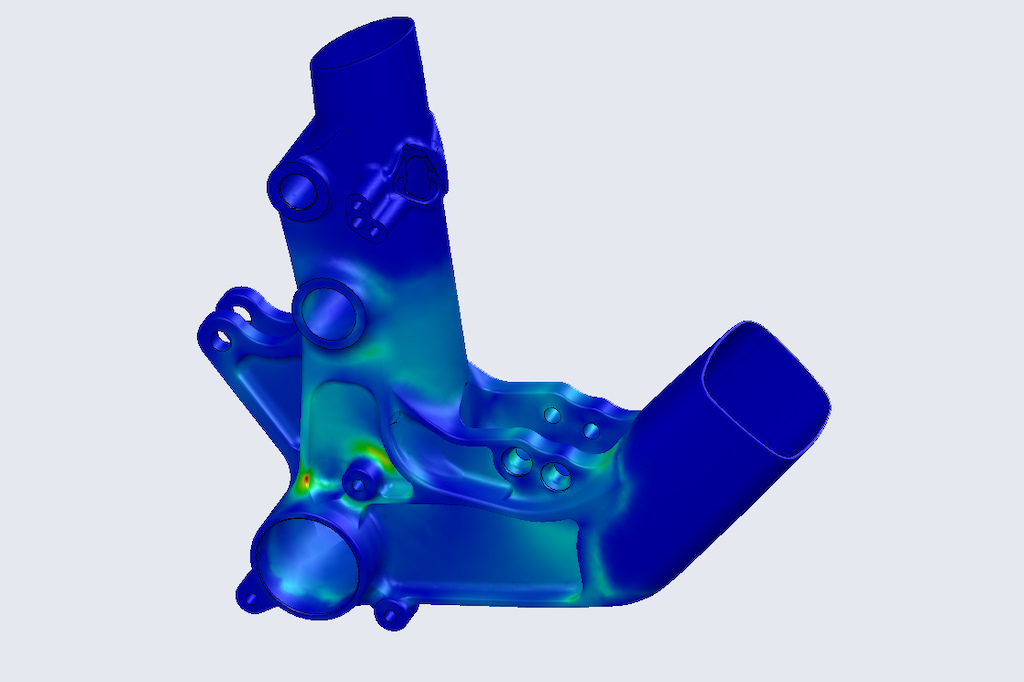

Really in simplest terms, it is a six bar DW6 bike, but one of the pivots is a flex stay.

Brian Park:

So the seat stay would be the flex stay in this case, yeah?

Kevin Tisue:

That’s correct. So they’re technically, I mean, if it was a true six bar, there would be a pivot back there on the seat stay down by the rear axle, probably.

Brian Park:

Oh god, so a five and a half bar is actually correct. Sh*t.

Bernard Kerr:

I love that.

Brian Park:

So it’s a DW6, which is what Atherton uses as well. [They] will be the obvious comparison for a lot of the things on this bike, even though there’s a lot of differences. Did you try other suspension designs in this process?

Kevin Tisue:

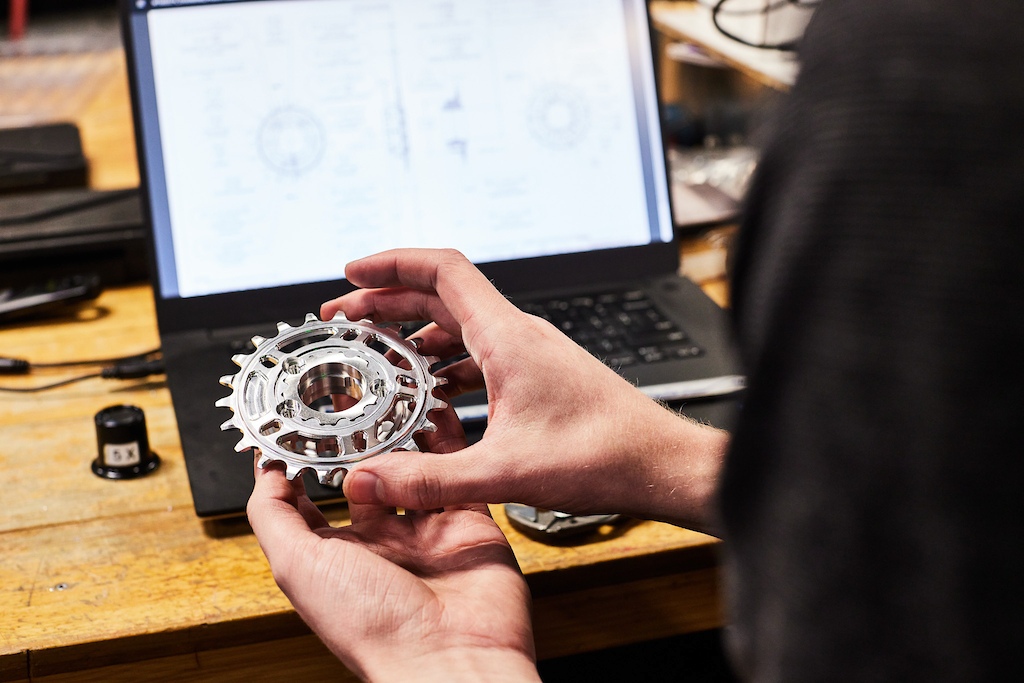

Yes, we actually built a complete other set of prototype bikes that were a standard DW Link four-bar bike with a little bit higher of a pivot built into it, but we didn’t do an idler or anything. So it was more like a Firebird built up into a downhill bike. So we tested, we built and tested two complete sets of prototypes for this. Again, another reason why we went to this system so we could do it so much quicker.

Bernard Kerr:

Like Kevin said, two complete bikes fully built. So we had the four bar and the six bar and they’re set up identical. They had every part the same, everything the same. I think I did 120 runs maybe between the two bikes on them in New Zealand. And Kevin flew out to New Zealand and came out for a couple of weeks and worked with us there. I’d honestly never had calluses as big on my hands. It was just downhill time, downhill. And it’s been such a cool process to be a part of.

Brian Park:

I’m just gonna make an assumption here. The fact that you’re riding at six bar right now, does that tell us which one was faster?

Bernard Kerr:

Yeah, we went backwards and forwards a lot, honestly. And it was really hard—it’s hard to replicate a World Cup track. That is a really, really hard thing to do. And especially comes finals day, even a World Cup track on the first day of practice to the third day of racing, one, two, three days changes a lot. And you need your bike to be best at the end of the third day, that’s when your bike has to work the best. And to replicate that anywhere in the world isn’t easy. New Zealand’s probably one of the best spots, but both bikes felt really good. But as soon as we started getting to the rougher tracks, and we were literally searching for the roughest parts of tracks to try and test these bikes on, we felt like the six bar just tracked better, braked better, and just carried speed through the rough stuff better.

It took a lot of time going backwards and forwards between the bikes. Between shock positions, headsets, rear axles, I think there was 16 versions of each frame, if you changed the shock here, but then put the headset here, but then put the rear axle here, there was 16 versions you could do of each bike. And we had two bikes. There’s 32 bikes you could make.

Henry Quinney:

Wow.

Bernard Kerr:

So between trying to change stuff backwards and forwards, it’s a huge process and a lot of runs to do. But we came to the conclusion that the six bar felt amazing and was just better on the rough stuff.

Brian Park:

I imagine that wasn’t necessarily an easy decision, Kevin, from an R&D standpoint, because so many of your other bikes have different DNA and there’s an advantage to having similar suspension platforms throughout your whole line, how did you feel about it? Were you hoping secretly in your heart of hearts that they would choose the four bar?

Kevin Tisue:

Absolutely. Yeah, to be 100% honest, I was really hoping it would be the four bar. We’ve been building four bar bikes for a long time and it’s a really good system. It’s robust and we know how to design a bike that way quickly and efficiently. Also you think of all the issues with all the extra pivots and chains and all of that. I had hoped for the four bar, but at the same time I’m super excited. I’ve been designing four bar bikes now for, 15, 16 years. I’m pretty stoked to be working on something new.

Henry Quinney:

So you mentioned the two chains there, which is a really important point. Hypothetically, let’s just imagine a world where to get sufficient chain wrap for an idler-equipped bike, imagine you had to sometimes make it really, really ugly. Your bike doesn’t suffer from this hypothetical problem. Was that an aesthetic thing? Was it a chain wrap issue? Was it a design parameters thing? Because it does look cleaner for it, even though it’s actually got the complication of two chains.

Brian Park:

I’m gonna jump in here and answer the questions because obviously, obviously, it’s a Brooklyn Machine Works tribute. Come on.

Kevin Tisue:

Hah! (laughs)

Bernard Kerr:

The Rubber Ducky! Literally childhood dreams, right?

Brian Park:

God, I don’t know. You go and you look at them now and they’re 30 feet tall and two feet long.

Bernard Kerr:

Hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehehe

hehehehehehehehehehehehehe

[Bernard didn’t actually laugh for five minutes, but our transcript service decided this is what he said and who am I to question it? –Ed.]

Kevin Tisue:

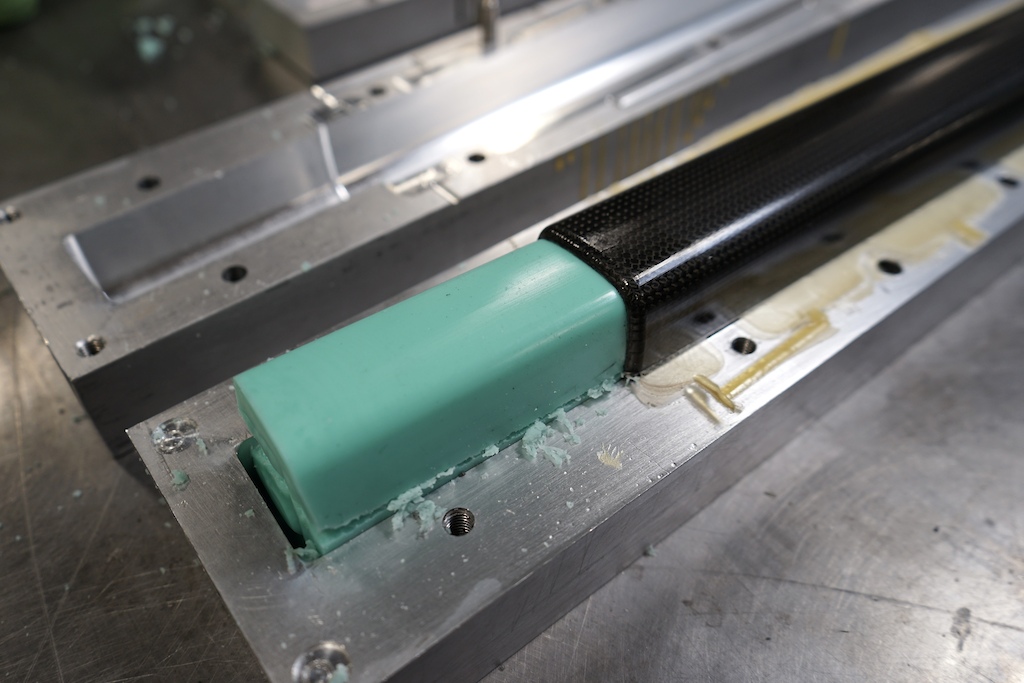

Definitely a really big consideration is chainring wear, all of that. It’s way, way better that way than doing an idler. Just having a little bit of chain wrap. So it’s just more reliable that way.

Somebody in the comments pointed out that, and I’m sorry I’m not giving you credit because I don’t remember who you are. Somebody asked about how the sprocket gets tensioned, how do you set chain tension on the one that doesn’t have a derailleur in the system? How does that second chain retain tension?

Bernard Kerr:

I read that. I thought it was funny when I read it. I was like, “I know this. I wonder when people are going to start finding out.” And someone smart kind of wrote down what it was, but Kevin would explain it way better than me right now.

Kevin Tisue:

Yeah, it’s a simple system. It’s just a little bit of an offset cam. So it’s a little eccentric, not on the bottom bracket, but on the sprocket end of things. You don’t need a lot of movement. You just need a little bit and we just get enough out of it.

Bernard Kerr:

And it’s been, I’ll jump in as well, it’s been so interesting, how easy Barnaby, my mechanic, has felt to work on that, because that was one of our big worries, “how are we gonna do this? Is it gonna be hard?” And you just nip it up. It literally needs no pressure. It locks on the other side. And we’ve worked with it as well in different conditions and just the perfect amount of tension because the chain’s so tiny as you can see. It’s super easy to dial it in. Not trying to show off for Pivot here, but we were kind of worried when we first thought about it, but it’s so dull and how easy to just nip it up. It’s really cool.

Henry Quinney:

And speaking of that area of the bike, I once heard many years ago that Dolly Parton came second in a Dolly Parton lookalike contest. Is it that somebody has made some Shimano Saint cranks that look more like Shimano Saint than actually Shimano make, or is that actually a new Shimano Saint crankset?

(awkward looks)

Kevin Tisue:

Those are some really good cranks on those bikes…

Bernard Kerr:

We’re going to have some great cranks soon. The great cranks are coming…

[it turns out they’re rebadged RaceFace Atlas cranks and we got all excited about nothing. Sorry.-Ed.]

Henry Quinney:

If we go back to, right back to sort of the inception of this bike, Bernard, we hear rumors maybe on the media side and some of that filters through, of a certain rider really wanting a high, high pivot bike. We hear other people like Santa Cruz saying they tried one and they didn’t like it, and there’s similar thing with Aaron Gwin and Neko Mulally doing all these different things now. And I think there’s a layer of transparency that we haven’t really had in downhill racing for a little while. When you heard about the option of this new suspension system with potentially a higher place pivot, was that something you were madly keen about or coming off your best season ever where you’re like whoa whoa, lads don’t change a bloody thing we’ve got this thing sorted.

Bernard Kerr:

No, honestly, I was super excited from the get go. The first time I heard about these new prototypes was last February. I was in Chile at a street race at the start of 2022. I had a phone call on Teams or Zoom, whatever the hell it was. But yes, I was in Chile at the beginning of 2022 and I saw the first drawings for this. That’s how long this has been in the works and Kevin and everyone’s been working crazy behind the scenes to make this happen and figure out where we can actually put a crank line and a chain ring.

I didn’t even question it. We were on the current bikes, obviously amazing. I did really well on it last year. It’s… an insane bike, but we’ve had it for four or five years. So when Kevin said last February, hey, I’ve got something to show you, it’s been exciting from day one. Honestly, I haven’t, I probably should question stuff more. I never do. I’m just always excited about a lot of things.

Brian Park:

Were you late for that call too?

Bernard Kerr:

(laughs) No, yeah, I missed it. I actually missed that call. I’m lying. Honestly, Matt and Eddie were on the call with Kevin and I wasn’t. I went on my own because I missed it. You’re not even wrong.

Kevin Tisue:

(laughs)

Brian Park:

Bernard, were you envious of some of the racers that had high pivots? Before you had the option of riding a high pivot, did you have high pivot envy?

Bernard Kerr:

Not really, I don’t know. Our current bike is so good and it’s so good at pumping. I think as tracks change, for everyday riding our current bike’s unbelievable. If you’re in bike park, if you’re riding downhill. But I think on the World Cup tracks we have now, which are so high speed, maybe, maybe this high pivot thing could be good. I did really good at Snowshoe last year, I got second. The next week at St. Anne. We turned up at St. Anne, it’s wet. I’m thinking, I’ve got this in the bag, man. St. Anne’s mine this week. Honestly, I couldn’t have been more confident. Timed practice comes around day one. It’s wet. I’m like, watch this. Honestly, so confident or cocky. However, people want to see it. I won time practice by almost three seconds. I’m thinking, just a nice run of that, man, I’m on. And as the track dried out, I was like, oh no, we just need some more rain. This track needs to stay slow. Cause I know what it gets like—St. Anne’s a high speed, rough track. When it gets that high speed and that rough, I was like, sh*t, these high pivot bikes, I know they’re going to come into their own a bit. I got fifth, but I did think the high pivots might’ve had a little fraction of an advantage on me there.

Brian Park:

How much faster was first place in Snowshoe?

Bernard Kerr:

At Snowshoe? 0.4.

Brian Park:

Do you think [the new bike] would have had 0.4?

Bernard Kerr:

I don’t know dude, that track’s got a lot of pumping and pedaling, but it also has a lot of rough chatter, a lot of rough in that flat rocks at the bottom. It’s hard to say, you’ll never know. But I don’t know man, it’s a tough one.

Henry Quinney:

As I think it was the comedian Jimmy Carr that said, the first bird gets the worm, but the second mouse gets the cheese. We’ve seen the Commencal go super high pivot, absolute truck bike and actually come lower [in the pivot placement]. You obviously had a good bike in the Firebird, the current generation, which is doing really well, riders love it. Do you think that actually having a bit of distance and seeing sort of where the conversation’s gone has been a benefit? Would you describe this bike as a true high pivot or is it like a medium pivot or? How would you describe it?

Kevin Tisue:

I would describe it as a medium. Yeah, there’s some weird things that happen with really high pivots that riders are certainly noticing. So, we purposefully did not go as high as we certainly could have.

Brian Park:

Is the bike that you’re riding now the same as what you were testing in New Zealand, or were there changes made between then and now?

Bernard Kerr:

The one I was on at Lenzerheide is new. We flew someone last week, Pivot has been going around the clock doing 14 hour days. We flew an amazing guy, Doug Tucker, huge shout out to him. He flew from the UK last week to America on a Wednesday, picked the bikes up from Pivot on Thursday and flew the bikes to Munich on Friday. That’s how late, so I got, that bike was hand delivered to Austria and picked up from pivot HQ in America last week, four days before Lenzerheide started.

Brian Park:

Kevin, what’s different about that bike?

Kevin Tisue:

Well, some of the geometry changed a little bit. Some of the parts that we had in there that allowed us to adjust everything around were pulled out to keep things a little simpler.

Brian Park:

Oh, so some of the several different shock mounting positions and axle length or chainstay lengths and that kind of thing?

Yep, yeah, some of that stuff changed, certainly got locked in a little bit for now, so we could have a little more reliable bike. It’s not that we had problems with the other ones coming loose, but you know how it is, the more complex you make stuff, you’d rather keep things simple. So there was that. And yeah, as Bernard said, we were in a mad rush to get that stuff done.

We even had Wolf Tooth make chain rings for us and everything because we didn’t have time to make them this round. And it was a big team effort all around really.

Brian Park:

And where did you end up on geometry for this prototype?

Kevin Tisue:

Um…

Bernard Kerr:

Ever-changing, developing.

Kevin Tisue:

Between these two versions we went shorter on reach. And we went with some of the shorter chainstay length options that we had. So, yeah.

Brian Park:

Interesting.

Henry Quinney:

Well Bernard, how does rear chainstay length affect the most important thing to you: doing horrible stoppies on massive jumps? Does it play at all or?

Bernard Kerr:

Yeah, it depends what we’re talking about. Like Kevin says, I always have such chats with people about are you trying to go faster or are you trying to have more fun? Honestly, I talk to people about that so much because for my downhill race bike, I wanna be as fast as possible, obviously, to win races. But on other things like in the fashion or things going backwards and forwards, I wanna be going as slow as possible whilst having as much fun as possible. So I’m as safe as possible whilst the biggest smile on my face. I don’t understand it all the time that people just want to go faster and faster. I want to go as slow as possible whilst having the most fun in a way, but obviously you want to hit big jumps and you want to be stable and you want to… It’s a tough one. Like, I don’t know, dude.

Because it’s a mullet now a mullet is easier to whip honestly yeah, realistically It’s just gonna be better and easier. I was so against 29er and I got used to it. I loved it full 29, but a lot of the World Cup guys can’t believe I was on full 29 last year doing that well at the end of the season, which is weird. But no, everything I’ve ridden it on feels great. I know definitely the first day on it we went up Skyline in Queenstown. There’s a trail called Huck Yeah and I almost crashed because I went off a lip and just did the same kind of flick. And even though the bike is definitely longer, but the rear wheel is small and light. I was sideways way more than I thought. And that was kind of like a shock to start with, but otherwise, no, she jumps good. She’s gonna go to Hardline. It’s gonna be on the top. The bike’s good, man.

Brian Park:

That was my next question. That’s the bike you’ll take to Hardline?

Bernard Kerr:

I don’t know, Chris, careful, we’ll have to ask this. Chris Cocalis, Pivot owner and founder was in Lenzerheide and he said, are you gonna ride this at Hardline? I said, you tell me, I want to. I think I’m allowed, but sometimes it’s hard to read Chris. (laughs)

Brian Park:

Just give him another Diet Coke and…

Bernard Kerr:

Coke Zero, not Diet Coke. It’s Coke Zero now, mate.

Kevin Tisue:

It is Coke Zero.

Brian Park:

I had dinner with him in Taiwan earlier this year. And then later that night, I was coming back from another event or something, and I just see Chris walking across the hotel lobby with a two liter of, I guess Coke Zero. I thought it was Diet Coke, but Coke Zero. And I was just like, that’s Chris.

Bernard Kerr:

Man, that’s Chris. Honestly, I said to the boys that we have a couple of my brother and a new guy called Steph that work for the team. I said, when you go to the store today for shopping, it’s Coke Zero’s bottles in the fridge, no one touches them. And then sure enough, Chris rolled up at the World Cup, gets out of his car, had a Coke Zero in hand. I was like, well, if you want a cold one, they’re in the fridge.

Brian Park:

Oh man, Bernard knows how to manage up.

Kevin Tisue:

(laughs)

Henry Quinney:

Let’s just talk about the manufacturing process. Brian, it’s one of your notes that you see here. Huge amount of machining hours. How long does one of those lugs take to machine?

Kevin Tisue:

I mean, just a single lug, you’re looking at, some of them are 16, 20 hours? For us, it’s all about managing our resources. We have lots of machines and really good machinists. Bill at Pivot has been there the whole time as well, and he’s amazing. We’ve figured out some great ways to make some really difficult parts to make.

Brian Park:

But when you’re making these, you’re really thinking about one-offs, prototypes, and not you’re not thinking about production efficiency because ultimately this isn’t how you, if and when in the future, if you take the learning from this to a consumer bike, this isn’t how you plan on making it.

Kevin Tisue:

Yeah, I mean, it’d be nice if we could make some like this, but it’s not that practical at the moment.

Brian Park:

If you look at the comments on, when Levy went down to the factory tour, I think the top comment was just like, “please God give us raw carbon and polished lugs, please please, I will give you all of the money.” What’s stopping you from doing that?

It’s something we have to look at, but there’s a lot of time that goes into each of those parts and it’s just not practical from a cost standpoint. I mean, at the same time, you can read a hundred comments on the same thread saying, Oh, I’m sure this will cost as much as my neighbors, BMW, you know? And so we have to find a balance there.

Brian Park:

I’m sure everybody who wants a one off, parametrically designed, custom geometry, polished lugs, raw carbon, made in USA everything and then they’re like, “Oh, sorry, that’s $26,000 for the frame? Oh, maybe not.”

Kevin Tisue:

Yeah.

Henry Quinney:

I’m sure you’ve worked with lots of really great racers. You probably have a whole raft of testers, a lot of, a lot of which probably fly under the radar, obviously local riders. Let’s do parents’ evening style report card. How does Bernard stack up as a tester?

Brian Park:

Most improved. That’s what he writes on the report card.

Bernard Kerr:

That’s true. I would agree with that. Most improved. Terrible before.

Kevin Tisue:

Yeah, well, he was a great tester in the beginning, we immediately knew we could send him stuff. And if it was going to get destroyed, he would be the one who could do it. He doesn’t quite ride like that anymore. I think his smoothness is improved. But back then, there was not much feedback. It was hard to get meaningful feedback on anything, but now I trust what I can get from him. So he’s actually great.

Brian Park:

Have you ever thrown them a curveball? Not told them which are the geo settings or which are the suspension settings and try and get some get some quote-unquote blind feedback?

Kevin Tisue:

Yeah, we did a little bit of that this time around. But I’ve also just forced him into trying things that he didn’t wanna try. Such as chainstay lengths.

Henry Quinney:

So in terms of that, that blind testing, something that we often get in the ski industry, they can go out and they can just take the top sheets off stuff and you don’t know what you’re skiing, right? And you can do different brands, do you think that because the bike is so vulnerable to our perception visually, we can see so much of what’s going on, do you think that undermines or makes testing to a degree harder, especially with something like a tire, right? Which is so obvious. You see it on the front and you know what’s going on. But even with our frame geometry, you can tend to get an idea of things.

Bernard Kerr:

I’ve got a bit of feedback here because from day one, well, last February, the only frame I saw that was going to be a prototype was the two chains six bar. We just got two chains. It’s cool.

Brian Park:

Is it the most expensiveist?

Henry Quinney:

(laughs)

Bernard Kerr:

We found out there was going to be a four bar as well. And honestly, I wanted the two chains to be so good out the gate. I was like, Oh my God, it looks so cool. And when I jumped in the four bar. It’s simple, it’s easy. It was so neat, dude. And I was like, I prefer the four bar. First day, two, three. It was just easy to ride. It felt so nimble with the mallet and stuff. All I wanted to do was prefer the six bar, the two chains. And I genuinely preferred the other one. I was like, sh*t, this sucks. I preferred the four bar, until we did more and more and more [testing].

So it kind of was blind without trying to be, even though you knew. I was like I prefer this one until we did so many laps, so many laps and you charge harder you start charging into the same rough section as you learn the new track more. We did so many laps on the same tracks like days and days and days in a row, and it was a real cool thing to be part of. It wasn’t quite fully blind, but you know what I mean.

Brian Park:

Most prototype bikes, when you see a prototype bike on Pinkbike or in the media or on Instagram or whatever, most of the time it’s, it might be a pilot run bike, but really the athlete had got the bike the week before it might be a slightly different layup than production, but it’s a bike that’s happening. It’s pre-production, but it’s happening. It’s done. The molds are paid for. It’s go time. And if the athlete has some feedback about the cable ports or something, maybe you can make a small mold modification, but if the athlete goes, “Oh sh*t, the BB is too low,” there’s nothing you can do.

Whereas this is actual an actual prototype, this will not see production. Kevin, if Bernard comes away from Lenzerheide with a request to change a head tube angle or chainstay length is it all parametric? Can you just update the model?

Kevin Tisue:

Yeah, we can have models at this point. We can have models change pretty quickly. But there’s still machine time and everything. So it’s not like a, it’s not like Bernard could show up this week in Leogang with a different bike.

It’s a bit of a rush. I mean, this last, the bikes that they’re racing right now were three to four weeks is what it took us to build all the parts.

Brian Park:

That’s insanely fast.

Bernard Kerr:

We can change them, which as you say, Brian, yeah, it’s not like when you see those new Santa Cruzes when Laurie and everyone was on them in New Zealand. They’re done, they’re a perfect carbon mold. They’re prototypes, but they’re not. They’re just pre-production, exactly what you say. Whereas if I said to Kevin, hey, in four weeks or five weeks, I want two degrees slack ahead angle, we could do it.

We had the bikes that got flown to Austria last week came with a new chain guide they put on it, a 3D printed chain guide. and instantly we’ve got too much flex. We’re not really sure, but we think this. Kevin and the crew and Bill in house from, I gave them the feedback on Sunday in Austria and they made a new part. They machined a new part in Phoenix and Chris Cocalis flew it to Lenzerheide for me. So from the weekend on Sunday, we had a different chain guide for the race. in Lenzerheide, which is insane. I don’t think I’ve ever heard of that in anyone else before.

Brian Park:

I think this is what consumers think happens for everybody every time in a prototype bike development.

Bernard Kerr:

No, that is insane. It’s ridiculous.

Henry Quinney:

I heard a rumour Bernard that last year you said that if you won a World Cup you’d retire. Is that true? And now you’re getting this new exciting bike, is that changing a bit?

Bernard Kerr:

No, I don’t know. It’s tough man. I maybe the sport is gnarly now. It’s super dangerous. It’s super high speed. This is my 16th World Cup season in a row.

Henry Quinney:

Well, hold on you’re gonna retire and I know for a fact you’re gonna go race moto.

Bernard Kerr:

I’m not going to race moto! I’m going to, I’m going to float about, do some whips and hang out that I’ve, I love World Cup racing, but we’ve taken a spin [in Leogang] and it looks like the same track. It’s the same track and I’m going to spend the same weekend in the same car park this year, which I am not complaining. I absolutely love my job, but it’s the 16th year in a row. I’m racing World Cups, which is a lot of seasons, racing as hard as you can. a bunch of weekends a year risking getting hurt and doing all this stuff. And we do only live once, man. There’s a lot of other amazing things I would love to do, whether it’s go film a video in Hawaii on the new pivot, go to Sri Lanka, go teach some kids how to ride in inner city London, whatever it is, there’s amazing things you can do in the world in cycling on YouTube now. So I don’t know. Yeah, I think if I won a World Cup, hopefully I don’t get fired by pivot. Hopefully I can still run the team. I think, yeah, man, I would be, I would be content.

I technically have won one World Cup in junior. We didn’t have a podium at the time, but the last ever race I did in junior, I won Schladming World Cup as a junior, but I’m not really counting that.

Brian Park:

Just to be clear, I would count the sh*t out of that. I’d be introducing myself like, “hey, my name is Brian. Also, did you know I won a World Cup once?”

Kevin Tisue:

(laughs)

Bernard Kerr:

No, man, I’ve got to win a World Cup. We’ve got so close now. This new prototype, it feels unreal. I feel like in the form of my life, I’ve been really sick last week leading into [Lenzerheide], super sick, trying to get all this dialed in and working way too much on the laptop, which I shouldn’t do. I’m pretty much a desk jockey half the time.

So everything’s in place now. I can chill and get off this podcast in a minute and go to bed before midnight, which will be nice. And I’m going to be healthy this week. And we’re going to charge boys. We’re going for it. I’m trying to retire as soon as possible. So I’ve got to win this bloody race!

Kevin Tisue:

ha!

Brian Park:

So I know we should probably let Bernard off pretty quick here so we can get his nap in and not blame this podcast for anything.

Bernard Kerr:

Pipe down! It’s 8.13. I’ll be fine.

Brian Park:

Hah okay, Kevin, before we end, I want to hear more about how we go from this bike to consumer reality. What’s the process like from here?

Kevin Tisue:

So, I mean, the way we run things is we run prototypes in parallel with design for production. And we have a production version of this bike in process already. Not in tooling or anything like that, but we have the industrial design going on it and the engineering part of it. We just keep that going on the sidelines until we’re ready, until we think everything is the way we want it, and until we’ve learned everything we feel like we want to learn from this. So how it goes is, we’ll go through whatever prototypes we need to do here, and then someday you’ll see Bernard on a production sample.

Brian Park:

And to be clear, right now we are talking about a more traditional looking carbon layout production thing.

Kevin Tisue:

Yeah, that’s what I’m talking about right now. Yes.

Brian Park:

So what then, compared to traditional test mules by welding a bunch of tubes together and then make a carbon bike from that. Is there an advantage to having carbon tubes in the mix in your prototypes?

Bernard Kerr:

It looks sick, come on! (laughs)

Kevin Tisue:

Yeah we can play with different stiffnesses a lot easier than just using aluminum tubes. We built aluminum prototypes for years and we’re pretty much stuck using stock aluminum tubes. It’s pretty rare that you would make new dies and everything for a new tube for a prototype and then make another set and another set just to change stuff around. But we can do that with carbon tubes. So there, there are big advantages to that for sure.

Brian Park:

I guess for brands that have aluminum models, they can use there’s a more direct line between the prototype and the final aluminum product, whereas to make a carbon bike, most brands out there are making an aluminum test mule and then it’s straight to production in carbon. Production is further from the prototype, I guess is what I’m saying, when you go from full aluminum to full carbon.

Kevin Tisue:

Yeah. It is, it’s a little further, yeah. We had a pretty good system of keeping our aluminum prototypes riding similar to our carbon bikes. It’s something you can’t really do necessarily in production because aluminum has to be stiffer if it’s gonna last a lifetime. But if you’re just doing prototypes, you can get away with a little bit less of. stiffness in some areas and get the bike to ride a little more like a carbon frame.

Brian Park:

Will your next generation of all of your other bikes use a similar prototyping process to what you’re doing with the downhill bike?

Kevin Tisue:

As of now, yes, but we’re also evolving the whole system. So we’ve got some more things coming down the line.

Henry Quinney:

I think that’s probably a really good place to leave the podcast. Thank you so much for coming on and giving us your time. Bernard, I know that now you’ve got an excuse in the back pocket if the weekend doesn’t go as well as you’d like, that we’ve kept you up until 8.30.

Bernard Kerr:

The weekend’s on boys, trust me. We’re charging. We’re making it happen!

Henry Quinney:

Thank you very much for listening and we’ll catch you next time on the Pinkbike Podcast.

Kevin Tisue:

Thank you guys.

Bernard Kerr:

Cheers.

Featuring a rotating cast of the editorial team and other guests, the Pinkbike podcast is a weekly update on all the latest stories from around the world of mountain biking, as well as some frank discussion about tech, racing, and everything in between.

Subscribe to the podcast via your preferred service (Apple, Spotify, RSS, LibSyn, etc.), or visit the Pinkbike Podcast tag page for the complete list of episodes.